Since the second half of the nineteenth century, thanks especially to the influence of the German historian Johann Gustav Droysen, it has become customary to refer to the period from the conquests of Alexander the Great to the Roman Empire – i.e., from the 4th century B.C. to the 5th century A.D. – as ‘Hellenism.’ A defining feature of this era was the emergence of large monarchies established by Alexander’s successors – not only in Macedonia, but also in Egypt under the Ptolemies, in Syria under the Seleucids, and later in Pergamum under the Attalids. Ruling over territories largely inhabited by non-Greek populations, these monarchs favored the construction of typically Greek buildings – such as theaters and gymnasiums – and fostered cultural institutions reminiscent of the philosophical schools of Athens. For reasons of prestige, they sought to attract renowned poets and intellectuals from various parts of the Greek world, including those known for their contributions to science.

Unfortunately, our knowledge of these institutions, their participants, and more broadly, the scientific activity in the capitals of the Hellenistic monarchies is limited. This is partly because such subjects were not a primary focus for ancient historians and scholars. Biographies of mathematicians and astronomers – unlike those of philosophers, for which Diogenes Laertius’ Lives remains an essential source – do not seem to have constituted a common literary genre. An exception is the biography of Archimedes, although it gained prominence chiefly due to his role in inventing war machines for the defense of Syracuse against Rome and his death during the city’s fall, which quickly became legendary. These events are recorded in the writings of historians like Polybius and Livy, and in Plutarch’s Life of Marcellus, the Roman general who conquered Syracuse. However, the biography of Archimedes by an otherwise unknown Heraclides has not survived, nor has the monograph on Alexandria by Callixenus of Rhodes, which, in any case, likely did not focus on the city’s scientific life. Celsus’ De medicina and various writings by Galen provide valuable insights into the theories and therapeutic practices of Hellenistic medical schools, though they only occasionally touch on the institutional context of medicine. Epigraphic evidence allows us to better define the status of physicians in Hellenistic and Roman cities. As for mathematics, primary sources such as the letters by Archimedes and Apollonius of Perga that introduce some of their works are of significant importance. Given the limited number of surviving sources, modern historians have tried to reconstruct the scientific institutions and activities of the Hellenistic period by relying on the few available texts and scattered references found in authors such as the geographer Strabo, the architect Vitruvius, scholars like Aulus Gellius and Athenaeus, and later commentators on the works of Euclid, Archimedes, and Apollonius, including Pappus, Proclus, and Eutocius.

The best-documented center is Alexandria, founded in Egypt by Alexander in 332 B.C. and becoming the seat of the Ptolemaic monarchy after his death. Among the many works of the Augustan-age grammarian Aristonicus of Alexandria, one is said to have been a monograph on the Museum of Alexandria (Photius, Bibliotheca, cod. 161, 104b 40-41), but it has not survived. Our main source on the Museum – literally a complex dedicated to the Muses – is a brief passage by Strabo (Geographica, XVII, 1, 8), who notes that in his time (around the start of the Christian era), it still formed part of the royal palace. The Museum included a promenade, an exedra with seats, and a large building (oêkos) where the scholars, or philólogoi, dined communally. The term sìnodos, used by Strabo to describe this group, suggests a kind of community, characterized by shared property, common meals, and the presence of a priest appointed specifically to the Museum – originally by the monarch, but in Strabo’s day by Caesar, likely Augustus.

The Museum is also attested by Suetonius for the reign of Claudius, and by Philostratus (Lives of the Sophists, I, 22 and 25) for that of Hadrian. Associated with the Museum, and likewise situated within the royal palace, was the greatest library of the ancient world, eventually containing, according to Aulus Gellius (Noctes Atticae, VII, 17, 3), up to 700,000 scrolls. It gathered Greek texts from across time and space, as well as Greek translations of foreign works, including the Old Testament. Galen (K XVII 1 601) recounts that Ptolemy II Philadelphus ordered the copying of books found on ships arriving at Alexandria, keeping the originals and returning the copies. Remarkably, the enormous ship constructed by Hieron II, king of Syracuse, under Archimedes’ supervision included a library; it was later gifted to Ptolemy (Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, V, 206d-209b).

The Alexandrian library was accessible mainly – perhaps exclusively – to Museum scholars and court members. A smaller library was later established at the Serapeum, a temple of the god Serapis, open to a broader, though still limited, public. At that time, reading was typically performed aloud in front of an audience, not silently and privately, and usually took place outside storage rooms, in exedras, porticos, or avenues. Over time, the library suffered repeated fires; one, during Emperor Aurelian’s campaign (270–275 CE), destroyed the Museum buildings, including those housing the library.

Already in the first half of the third century B.C., the learned poet Callimachus had compiled a kind of catalogue – the Pínakes – a true biobibliography in 120 books listing the writings of those who had distinguished themselves in various cultural fields (paideía). Such a work could only have been realized with access to the vast resources of the Library of Alexandria. It is difficult to ascertain whether this ‘catalogue’ also included authors of mathematical and astronomical texts, and whether a canon of ‘classical’ authors was established for the scientific disciplines in Alexandrian culture, as was the case for tragedians, comedians, orators, and historians. It is, however, likely that the library did contain scientific works. This appears plausible especially for the corpus of medical writings attributed to Hippocrates. Various physicians influenced by Herophilus – active in Alexandria in the first half of the third century B.C. – began compiling lexicons and commentaries on Hippocratic texts, probably based on the copies preserved in the library. According to Galen, Bacchus of Tanagra drew on word collections by Aristophanes of Byzantium, Eratosthenes’ successor as director of the Library, to construct his Hippocratic lexicon.

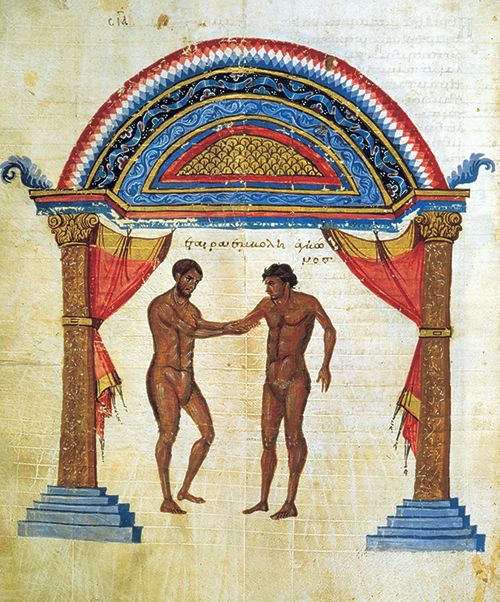

Such philological interests on the part of physicians presuppose the development of critical methods applied by Alexandrian grammarians to literary texts – primarily Homeric poetry – in order to reconstruct their most authentic versions. It is likely that medicine was among the first disciplines to adopt these methods and promote the practice of scientific commentary. As far as mathematics is concerned, this practice is fully attested only in later works, such as those of Pappus, and in the commentaries by Proclus and Eutocius on the writings of Euclid, Archimedes, and Apollonius of Perge. In any case, the only extant medical commentary from the Hellenistic age is Apollonius of Citium’s commentary on the Hippocratic On Joints, dating from the first century B.C.

The existence of a library was invaluable for this type of scholarly work, and the same can be said for the development of disciplinary histories. This endeavor had already begun in Aristotle’s Lyceum, through Eudemus of Rhodes’ histories of geometry and astronomy, and Meno’s history of medicine – later used in the so-called Anonymus Londiniensis. Within this context of a scientific culture grounded in books, we also find the literature concerning the hairéseis (medical and philosophical schools of thought) and the diadochaí (successions of prominent figures in the various philosophical traditions). It is no coincidence that the originators of these genres were two figures from Alexandria: Sozion in philosophy and Serapion in medicine, active in the late third century B.C. and associated with the empiricist school. Serapion’s literary model would later be continued by other empiricists, such as Glaucias of Tarentum, Alexander of Antioch, and Heraclides of Tarentum, as well as by the followers of Herophilus.

The establishment of the Museum and Library of Alexandria was not an abrupt innovation by the early Ptolemies. The cult of the Muses was already present in the philosophical schools of Athens in the fourth century B.C. In Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laërtius mentions the will of Theophrastus, head of the Aristotelian Lyceum, which refers to a sacred building within the school. According to Athenaeus (XII, 547d–548b), during Lyco’s leadership, the Lyceum featured a garden, a promenade, statues, and near the garden, a building (oikía) where members of the school dined communally. There was also a museum and a library intended not only to collect works written by the school’s members but also those used in their research. It can be reasonably assumed that the Museum of Alexandria was inspired by the Aristotelian school, particularly given the role of Demetrius of Phalerum, a pro-Macedonian who governed Athens from 317 to 307 and maintained close ties with the Lyceum (he enabled the foreign-born Theophrastus to acquire property in Athens). After being exiled, Demetrius took refuge in Alexandria, where he became an adviser to Ptolemy I Soter. It is plausible that he advised the creation of the Museum as a scholarly hub with a library, analogous to the Lyceum. Further confirmation of this connection comes from the fact that Strato of Lampsacus, before succeeding Theophrastus as head of the Lyceum, spent an extended period in Alexandria as tutor to Ptolemy’s son, the future Philadelphus.

Alexandria, however, was not unique. In Pella, capital of the Macedonian kingdom, Antigonus Gonatas (283–238 B.C.) also founded a library, which Aemilius Paulus brought to Rome after defeating the Macedonians in 168 B.C. Similarly, in 70 B.C., Lucullus transferred to Rome the library of Mithridates, king of Pontus. In Pergamum, perhaps under Eumenes II (197–158 B.C.), a large library was established in the temple of Athena Polias, which by the time of Mark Antony is said to have held about 200,000 scrolls (Plutarch, Antonius, 58.9–59.1). A series of inscriptions also attests, from the second century B.C. onward, to the presence of libraries in Rhodes and in gymnasiums – educational centers for ephebes – in cities like Athens, Kos, and Pergamum. This phenomenon continued in Rome, where in the first century B.C., wealthy individuals such as Varro, Atticus, and Cicero created personal libraries. Julius Caesar had planned a public library, entrusting the task to Varro; the project was completed in 38 B.C. by Asinius Pollio. Augustus pursued similar initiatives after 23 B.C., and the emperor Trajan later founded the Bibliotheca Ulpia in the Forum of Trajan. Both libraries had sections in Latin and Greek. In the early centuries of the Empire, many provincial cities also developed libraries – in Ephesus, Prusa, and Timgad (in Africa), for instance. In Athens, Emperor Hadrian, in his effort to promote Hellenic culture, established both a museum and a library (Eusebius, Chronicon, 227). This proliferation of libraries paralleled the increasingly cosmopolitan scope of scientific inquiry in the ancient world.

Who were the philólogoi, the members of the Museum of Alexandria? Strabo, in the passage previously cited, does not specify or name individuals, and Timon of Phlius, a disciple of the skeptic Pyrrho, is said to have mocked the ‘philosophers’ nurtured in the Museum, likening them to rare, luxurious birds who, surrounded by books, peck at each other in the Muses’ cage (Athenaeus, I, 22d). Timon also does not mention names, though it is unlikely that he was referring solely to philosophers in the strict sense. Indeed, the Hellenistic monarchs only rarely succeeded in attracting philosophers to their courts, and never those associated with the Athenian schools, despite maintaining positive relations with them and offering gifts and honors. As for the Peripatetic school, a notable exception – already mentioned – is Straton of Lampsacus, though his stay in Alexandria preceded his succession of Theophrastus as head of the school in Athens. Theophrastus himself declined Ptolemy II’s invitation to come to Alexandria, as did the Stoics Cleanthes and Chrysippus (Diogenes Laërtius, V, 37; VII, 185). Cleanthes sent Sphaerus in his place; the latter accompanied King Cleomenes of Sparta, after his defeat at Sellasia in 222 B.C., to the court of Ptolemy IV Philopator (Diogenes Laërtius, VI, 177). Similar failures marked the efforts of Antigonus Gonatas, king of Macedonia, to bring Zeno, the founder of the Stoa, to his court, and those of the Attalids of Pergamum with Arcesilaus and Lacydes, leaders of the Academy. In these cases too, Zeno sent Perseus and Arcesilaus dispatched Archias in their stead. Nor can the fact that the Epicurean Colotes dedicated one of his polemical writings to Ptolemy II be taken as proof of his presence in Alexandria. All of this indicates that philosophers continued to consider Athens the undisputed center of philosophical life and were reluctant to leave it. The situation was quite different, however, for scholars in the scientific disciplines.

A brief mention in Athenaeus (IV, 184b–c) provides further insight into who the philólogoi mentioned by Strabo may have been. In 145 B.C., upon the death of Ptolemy VI Philometor, a wave of intellectuals was expelled from Alexandria by his successor. As a result, Greek cities and islands were flooded with displaced grammarians, philosophers, geometers, musicians, painters, gymnastics instructors, physicians, and many other technêtai, who, impoverished, were forced to make a living by teaching what they knew. This account suggests that the Museum’s residents not only enjoyed communal meals but also received a stipend from the king (Athenaeus, XI, 494a–b; XII, 552c), enabling them to dedicate themselves entirely to research without being burdened by teaching responsibilities – though nothing prevented them from having students.

It is notable that Athenaeus’s list of intellectuals includes surveyors, physicians, and other technêtai. This too echoes a precedent set by philosophical schools such as the Academy and the Lyceum. According to Dicearchus, a pupil of Aristotle, mathematical research – including studies in optics and mechanics – was already underway in Plato’s Academy (Philodemus, Papiri Herculanenses 1021, col. Y, 1–17). The Academy also hosted astronomers and mathematicians like Eudoxus of Cnidus, Menaechmus, and Amphinomus. Aristotle’s investigations in biology and zoology are well known, and Theophrastus expanded them to include botany and the study of metals and stones. The crucial difference with the Museum, however, lies in the institutional model. While the philosophical schools were private initiatives – without civic funding and dependent on individual efforts and finances – the Museum was entirely under royal patronage. This included the appointment of librarians (many of whom also tutored the royal children), the recruitment and support of scholars, as well as the acquisition of books, research instruments (such as those for astronomical observations), and even a zoological collection (Athenaeus, XIV, 654b–c). The most extraordinary case of royal sponsorship relates to medicine. In the preface to De medicina (par. 23), Celsus reports that Herophilus and Erasistratus performed vivisections on living prisoners made available by the early Ptolemies. Tertullian (De anima, X, 4) even mentions 600 victims in the case of Herophilus. Galen’s silence on this point does not discredit Celsus’s account, which is instead supported by the remarkable anatomical findings these physicians made concerning the brain and heart valves.

That said, royal patronage was motivated not primarily by a desire to advance knowledge or benefit future patients, but by the prestige that came with such support. In the case of Mithridates, king of Pontus in the 1st century B.C., the use of condemned criminals to test drugs served his personal interest: to obtain antidotes and immunize himself against artificial and natural poisons. According to Galen (K XIV 2, 3 ff.), he ultimately had to die by the sword, as no poison could affect him. Vivisection was soon criticized by other physicians as both cruel and unnecessary. They observed that anatomical and physiological insights could be obtained by examining the wounded – gladiators, for instance. Even in these cases, however, it is likely that public authorities facilitated access to such bodies. In any event, vivisection fell into disuse, and Cicero (Academica, II, 122) refers to it as an outdated practice. This did not mean that anatomical studies – especially on animals – ceased in Alexandria; indeed, Galen notes that in the second century CE, he felt it necessary to go to the city to refine his skills in this domain (Anatomicae administrationes, I, 2; K II 220–222).

Among the librarians of Alexandria, the most significant figure for the history of science is Eratosthenes, a native of Cyrene – a city under Ptolemaic control, also the birthplace of Callimachus, and already associated with the mathematician Theodorus, mentioned by Plato in the Theaetetus. Before settling in Alexandria in 245 B.C., having been invited by the king also as tutor to his son, Eratosthenes had spent many years in Athens, where he attended the Stoa and, above all, the skeptical Academy led by Arcesilaus (Strabo, I, 2, 2). Because of the breadth of his scientific interests – from geography (a term he perhaps coined) to astronomy and geometry – he was nicknamed Pentathlos, but also Beta, to suggest that he had never achieved preeminence in any field, always remaining “second best.” Archimedes addressed two writings to Eratosthenes that have survived: The Cattle Problem and The Method of Mechanical Theorems, acknowledging in him both a philosopher of merit and an admirer of mathematical theory. His role as librarian was not incidental to his scholarly activity; indeed, considering that geography is a knowledge with a historical dimension, Eratosthenes composed a history of geography, in which he notably criticized Homer for his polymathía – that is, an encyclopedic type of knowledge lacking direct experience – contrasting it with the firsthand observations of Pytheas of Massalia (Strabo, II, 1, 5). In geometry as well, Eratosthenes reconstructed the history of attempts to solve the problem of cube duplication, culminating in his own contribution (Eutocius, Commentarii in libros de sphaera et cylindro, in Archimedes, Opera omnia, III, 88.3–96.27, ed. Heiberg). His map – designed according to geometric principles – was conceived less as a navigational tool than as a scholarly artifact for discussion and revision, much like the diórthüsis of Homeric texts performed by Alexandrian philologists. Royal patronage also played a role in Eratosthenes’ most renowned achievement: the measurement of the Earth’s circumference. He based this on the distance between Alexandria and Syene (Aswan), provided by the bämatistaí – land surveyors likely placed at his disposal by the king – and on readings taken with a gnomon, probably located within the Museum or royal palace.

While Eratosthenes’ close relationship with the monarch is well documented, the same cannot be said for other scientists associated with Alexandria. In his Commentary on the First Book of Euclid’s Elements (68.6–23), Proclus, writing in the fifth century CE, presents Euclid as a Platonist and recounts an anecdote in which Ptolemy I asks whether there is a royal road to geometry, to which Euclid replies that no such path exists. Euclid’s alleged link to Platonic philosophy, however, originates from Proclus or his sources and is based on the interpretation that the Elements culminate in the construction of the Platonic solids described in the Timaeus. There is no evidence that Euclid studied at the Academy in Athens. Moreover, the same anecdote is attributed to the geometer Menaechmus in response to Alexander the Great (Stobaeus, Anthologium, II, XXXI, 115, p. 228.30–33). It is generally accepted that Euclid taught in Alexandria, where, according to Pappus (Collectio mathematica, VII, 35), Apollonius of Perge is said to have studied under him. Eutocius (Commentaria in Conica, II, 168.5 ff.) places Apollonius’ activity during the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes (246–221 B.C.), at a time when Perge, a city in Pamphylia, was under Ptolemaic rule.

This suggests that Alexandria hosted not only established scholars but also students from other parts of the Greek world, attending lectures or participating in research. From Samos – also under Ptolemaic control in the third century B.C. – came the astronomer Aristarchus, who likely studied in Alexandria under the Peripatetic philosopher Straton (Aetius, I, 16, 5). Another Samian, the astronomer Conon – highly esteemed by Archimedes – may have met him during one of his stays in Alexandria. Conon is also cited by Apollonius of Perge among those who had previously worked on conics. His closeness to the court is implied by his naming of the constellation ‘Berenice’s Hair’ in honor of the wife of Ptolemy III Euergetes – a name later immortalized by Callimachus’ poem. Conon also formed a circle of disciples, among them Dositheus of Pelusium, to whom Archimedes addressed some of his writings after Conon’s death. Hipparchus of Nicaea in Bithynia – whom Ptolemy mentions in the Syntaxis or Almagest (I, pp. 195–196, ed. Heiberg) – is recorded as having made an astronomical observation there in 146 B.C., and notes the existence of a bronze armillary sphere in Alexandria’s Square Stoa, used for equinox observations.

The installation of astronomical instruments in public spaces may have been another manifestation of royal patronage, serving both scholarly and prestige purposes. But Alexandria also possessed instruments crafted by astronomers themselves: diopters, armillary spheres, and others described by Ptolemy. This does not imply that all astronomers and surveyors came from elsewhere; some, like Hypsicles – likely born in Alexandria in the second century B.C. – conducted their research there. Hypsicles authored On Ascensions, based on local observations, and the so-called Book XIV of the Elements, both of which survive. Other Alexandrian figures include Sosigenes, who assisted Julius Caesar in 46 B.C. with calendar reform (Pliny, Naturalis historia, XVIII, 57.211) and likely accompanied Cleopatra to Rome; Menelaus of Alexandria, active in the first century A.D. and author of a treatise on spherical geometry; and Ptolemy himself, in the second century A.D. These cases confirm the sustained tradition of mathematical and astronomical study in Alexandria over centuries. However, this does not mean that all such scholars belonged to the Museum or that they could not work independently while accessing the Library. Nor should one assume that Alexandrian-affiliated mathematicians and astronomers operated exclusively in the city. Archimedes conducted his work primarily in his native Syracuse, under the patronage of Hieron, who, according to Plutarch, urged him to pursue practical applications as well. Hipparchus favored Rhodes for his astronomical research (Strabo, II, 1, 5). Conon, according to Ptolemy’s Phases of the Fixed Stars (Opera omnia, II, pp. 66–67, ed. Heiberg), had also conducted observations in Italy and Sicily – perhaps where he met Archimedes. In the preface to Book I of the Conics, Apollonius of Perge mentions having worked in Alexandria, where he was joined by the surveyor Naucrates, but also being active in Pergamum with Eudemus, the recipient of his work. Diocles, author of On Burning Mirrors (preserved only in Arabic) and active between the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C., was in Arcadia – an area not known for scientific activity – when the astronomer Zenodorus posed to him the question that led to the writing, which responded to earlier problems formulated by Pythion for Conon and Zenodorus.

If mathematicians and astronomers could benefit from Ptolemaic support mainly due to the prestige they conferred in the eyes of the Greek world – and in the context of competition among Hellenistic monarchs – more direct utility could be derived from the work of technicians, geographers, and physicians. This is particularly evident in the realm of military technology. In his treatise Belopoeica (4.3, p. 50, 37–40), Philo of Byzantium, who lived in the 3rd century B.C., explicitly states that whereas the ancients were unable to determine precisely the diameter of the orifice for the tension rope in catapults, Alexandrian technicians had recently succeeded in doing so. This was thanks to the means made available to them by kings who were philódoxoi (lovers of fame) and philótechnoi (lovers of technique), enabling them to conduct experiments that were not random, but methodically planned and repeated.

This phenomenon was by no means limited to Alexandria. Philo himself (4.5, p. 51, 15–23) mentions his work both in Alexandria and in Rhodes. Biton’s treatise on siege techniques (polyorecetics), possibly dating to the early 2nd century B.C., was dedicated to King Attalus of Pergamum (Athenaeus, XIV, 634a). Moreover, there are cases of rulers who personally oversaw military engineering projects – such as Demetrius, celebrated in Plutarch’s biography and nicknamed Poliorcetes, the ‘besieger of cities,’ and Dionysius, tyrant of Syracuse. As early as the first half of the 4th century B.C., Dionysius had attracted top technicians from Italy, Greece, and even Carthaginian territories (Diodorus Siculus, XIV, 41.3; 42.1; 50.4).

It is no coincidence that Archimedes developed his war machines in Syracuse under the patronage of Hieron (270–216 B.C.). Rhodes also had a strong tradition in military technology. Vitruvius (X, 16.3) cites numerous architects from that island who received public stipends for their work. He himself held public office in Rome and dedicated his De architectura to the emperor – probably Augustus, though he is never mentioned by name. The value placed on technically trained officials in the early Roman Empire is exemplified by De aquaeductu urbis Romae, authored by Sextus Julius Frontinus. Appointed curator aquarum by Emperor Nerva in 97 C.E., Frontinus conducted first-hand assessments of Rome’s aqueducts, analyzing pipe systems, delivery capacities, and the legislation governing their upkeep – without seeing this as beneath his dignity as a member of the elite.

Attention to technical matters was not merely utilitarian; it also conferred prestige upon kings and emperors through the creation of marvels meant to be displayed and admired. We’ve already mentioned the great ship built by King Hieron of Syracuse, designed more for spectacle than for navigation. Similarly, Ptolemy IV Philopator constructed a colossal ship in the late 3rd century B.C., which Plutarch described as “not very different from a building on land” (Demetrius, 43.5–6). This interest in spectacular devices is found also in the Pneumatica of Heron of Alexandria, who lived in the first century A.D. and drew on an older tradition going back to Ctesibius of Alexandria (active in the early 3rd century B.C.). Ctesibius was credited with inventing both a water-lifting device and a hydraulic organ (Vitruvius, X, 7.1–4). Using air or water pressure as a driving force, engineers created fountains spouting from statues, instruments emitting sounds, and mechanisms producing automatic fire ignitions. Mechanical theaters, featuring automata – moving figurines – were made possible by devices of the kind Heron describes in his Automata, where Philo of Byzantium is also mentioned as a forerunner.

Such pneumatic and mechanical devices were employed in temples and religious ceremonies, including royal processions where sovereigns demonstrated their splendor and power to astonish. Callixenus of Rhodes, in his account of Alexandria under Ptolemy II Philadelphus (around 271–270 B.C.), described a parade of exotic beings, objects, and animals, including a statue that, mounted on a chariot, rose mechanically, poured milk from a golden jug, and returned to its seat (Athenaeus, V, 197–203b). It is telling that Demetrius of Phalerum, adviser to the Ptolemies, had previously used a similar automaton in a procession in Athens (Polybius, XII, 13.7 ff.).

Geographical literature, also serving monarchic and imperial power over vast territories, blended utility and wonder. It furnished maps and territorial knowledge vital for navigation and military action, while also offering accounts of exotic locales, flora, fauna, and peoples. Agatharchides of Cnidus – a city under Ptolemaic control – was secretary to Ptolemy VI and drew on official documents preserved in royal archives to provide geographic and ethnographic accounts of Africa and Arabia. Strabo, in his Geography (I, 1–2), explicitly acknowledged its political purpose. An admirer of Rome’s greatness (V, 3, 7–8), he believed that the emergence of a single empire under Rome had enabled the advancement of knowledge beyond the circle of specialists.

Shortly before Strabo’s time, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa had commissioned a map of the empire to be inscribed on a wall of the Porticus Pollae for public viewing. Augustus himself tasked Dionysius of Charax with producing a commentary on the East for his nephew Gaius (Pliny, VI, 141). Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History (II, 117–118; XIV, 1–7), credited the empire with fostering peace and exchange – and thereby knowledge – but also lamented a decline in scientific impetus. He blamed this on a loss of competitive patronage among the reges innumeri (the many kings) of the Hellenistic world, from which earlier cultural advancements had sprung.

In medicine, relations with power in the Hellenistic and Roman periods varied. Alongside itinerant physicians focused on therapeutic practice were court doctors and researchers engaged primarily in theoretical inquiries into anatomy and physiology – fields not always yielding immediate practical results. Among the latter were Herophilus and Erasistratus, who, as noted, benefited from Ptolemaic patronage, though the sources do not explicitly confirm that they were salaried members of the Museum. Herophilus, from Chalcedon on the Bosphorus, is linked to Alexandria only indirectly: through Celsus’ account and his use of the term pharoid to describe a muscle oriented toward the tongue – presumably referencing the Lighthouse of Alexandria, built around 280 B.C.

Erasistratus, by contrast, is mentioned in several ancient sources as having connections to the Aristotelian school in Athens, where he reportedly studied under Theophrastus (Diogenes Laërtius, V, 57). An anecdote also places him as court physician in Antioch for the Seleucid dynasty: through pulse analysis, he allegedly diagnosed the lovesickness of the young Antiochus I Soter for his stepmother Stratonice, daughter of Demetrius Poliorcetes and wife of Seleucus. However, Pliny attributes the story to Cleombrotus – possibly Erasistratus’ father – and Valerius Maximus hesitates between Erasistratus and a mathematician named Leptines (Facta et dicta memorabilia, V, 7, ext. 1). In any case, this tale does not preclude Erasistratus’s possible activity in Alexandria as well.

According to Galen (De placitis Hippocratis et Platonis), in his old age Erasistratus abandoned therapeutic practice to devote himself exclusively to scientific investigation, particularly by conducting dissections – an activity that, according to Galen, he pursued in Alexandria. However, the report that he was buried on a peninsula facing the island of Samos suggests that he eventually ceased to reside in Alexandria. It is likely that, like many of his fellow physicians, Erasistratus led an itinerant life, even if he spent a long period permanently based in Alexandria.

The city, in fact, attracted physicians not only from traditional medical centers such as Kos and Cnidus – both of which had fallen under Ptolemaic influence or control – but also from other parts of the Greek world. Many physicians who drew on the teachings of Herophilus were active in Alexandria. Polybius (XII, 25, d 4) cites them as paradigmatic examples of doctors who based their medical knowledge primarily on books. Among them was Andreas of Carystus, personal physician to Ptolemy IV Philopator, who died during the Syrian War in 217 B.C. in the king’s tent, killed by a traitor who had not found the king there (Polybius, V, 81.1–6).

Even after the intellectual diaspora of 145 B.C., Herophilean physicians continued to work in Alexandria, though from the 1st century B.C. onward, their influence spread to Asia Minor as well. Similarly, the legacy of Erasistratus lived on both in Alexandria and in Seleucia, where Apollophanes served as physician to Antiochus III (224–187 B.C.), demonstrating a continued connection with the Seleucid court – the same context in which the anecdote about Erasistratus had originally been set.

In the 1st century B.C., an Erasistratean school led by Icesios of Smyrna operated in Skion, and by the 2nd century C.E., Galen attests to the presence of erasistrateî in Rome. These followers, who claimed a privileged link between their founder and the Aristotelian tradition, were known for their unrestrained use of bloodletting.

A parallel case can be made for the empiricist school of medicine, whose founder, according to one version, was Philinus of Cos – a direct student of Herophilus – and according to another, Serapion of Alexandria, already mentioned earlier. From its beginnings, Alexandria served as a central hub for this school’s activity, though we have reports from as early as the 2nd century B.C. of empiricists from Tarentum, Antioch, and Cyrene.

The aforementioned commentary by Apollonius of Citium on the Hippocratic treatise On Joints is dedicated to a certain Ptolemy, likely Ptolemy XII Auletes or his brother, then ruling over Cyprus (between 80 and 58 B.C.). Apollonius himself notes that he attended lectures in Alexandria by a physician named Zopyrus. Nor is it surprising to find physicians present at the court of Mithridates in the 1st century B.C., alongside the botanist and pharmacologist Crateuas.

The existence of medical schools (didaskaleîa) is attested in various parts of the Greek world – unsurprising, given that medical practice, unlike other scientific pursuits, was inherently tied to the care of patients and thus naturally lent itself to forms of institutional organization for the training of practitioners. This institutional aspect is further confirmed not only by the proliferation of instructional texts, but also by the existence of writings specifically intended for beginners, as is the case with some of Galen’s own works.

Mathematics – especially geometry – was the field in which scientific activity first acquired a fundamentally unified and cumulative structure. Euclid’s Elements, composed around 300 BCE, presented – albeit in a form neither perfect nor complete – numerous results of earlier research in plane and solid geometry, as well as in the theory of numbers and proportions, all framed within an axiomatic-deductive system. The work consists of propositions derived from a small set of initial principles (definitions, common notions, postulates) or from propositions previously demonstrated. It would be mistaken to consider Euclid the inventor of this expository form. Proclus refers to several of his predecessors, and examples of this structure are already found in extant works predating the Elements, such as those on spherical astronomy by Autolycus of Pitane and Book III of Harmonics by Aristoxenus of Tarentum, a pupil of Aristotle.

Ancient mathematicians, both before and after Euclid, employed other heuristic methods beyond the axiomatic-deductive form – for instance, the analytic method, especially in solving quadratic and cubic equations. Archimedes himself distinguished his mechanical method, which he regarded as heuristic, from the strict geometrical demonstration. Nevertheless, post-Euclidean mathematicians never questioned the deductive structure of geometrical knowledge or the necessity of deriving propositions from pre-established principles. This is not to say that disagreements did not arise; on the contrary, mathematicians debated heuristic strategies, proposed alternative demonstrations they considered superior to Euclid’s, or disputed the deductive placement of certain propositions, such as whether a given statement should count as a principle or could be demonstrated.

Traces of these debates appear in Proclus’ commentary on Euclid. Apollonius of Perge, for instance, attempted to prove Euclid’s first common notion – that things equal to the same thing are equal to each other – while Ptolemy is said to have written a treatise dedicated to the postulate of parallels. These discussions, however, focused not on the truth or falsity of Euclidean axioms, but rather on their status as foundational principles. This line of inquiry is also attested in the Definitions attributed to Pseudo-Heron, which explores alternative ways of defining geometric entities.

Terminological instability likewise persisted beyond Euclid, and is evident in the writings of both Archimedes and Apollonius. Yet we find no record of any ancient mathematician contesting the validity of Euclidean deduction itself. On the contrary, the power of this model is demonstrated by its extension to other scientific domains: in music (e.g., Aristoxenus’ Harmonics and Euclid’s Sectio canonis), astronomy (e.g., Euclid’s Phaenomena and Aristarchus of Samos’ On the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and Moon), and even theology in Late Antiquity, as shown by Proclus’ Elements of Theology.

The broad acceptance of a common model enabled a form of intellectual cooperation among mathematicians, even those geographically dispersed – a collaboration documented in the introductory letters of Archimedes, Apollonius, and Diocles. Archimedes’ letters to Dositheus, a student of Conon in Alexandria, and to Eratosthenes do not systematize others’ results, but rather communicate original findings, sometimes including the process by which they were obtained. Occasionally, the letters present problems or propositions with requests for solutions or demonstrations. Archimedes viewed scholarly exchange as valuable, believing that interlocutors might offer meaningful contributions – he even laments Conon’s untimely death in this regard. Pythion of Thasos had once written to Conon to pose a question about burning mirrors, as Diocles recalls.

The role of other mathematicians thus encompassed not only collaboration in ongoing research but also the validation of new results. In the preface to Book I of the Conics, Apollonius describes this small, close-knit community as responsible for such assessments. For Archimedes, the object of a competent mathematician’s judgment is the proof itself. In a Euclidean axiomatic system, validating a proof entails verifying its coherence with the accepted axioms and the admissibility of those axioms. When successful, this validation confers pístis – the assurance or trust in a demonstration’s soundness – as Archimedes states in his prefaces to Quadrature of the Parabola and the Arenarius. The integration of new propositions into the edifice of geometric knowledge presupposes a shared and somewhat codified tradition. The mathematical community, understood as a network of cooperation and mutual oversight, is thus inseparable from the concept of tradition. This underpins a conception of geometrical progress as a cumulative accumulation of results, codified by Euclid but traceable, for Archimedes, as far back as Eudoxus.

Archimedes, aware of having discovered the quadrature of the parabola, did so not by introducing new axioms, but by building on earlier ones that had already proven fruitful. Diocles affirms a similar principle in the preface to his treatise On Burning Mirrors: novelty is fully compatible with continuity. The prefaces to Apollonius’ Conics depict a community of mathematicians working in different locations, sharing and disseminating their results – even in early forms to be later refined. Apollonius himself acknowledges that it is the demonstrations that give his results their value. Basilides of Tyre collaborated with the father of Hypsicles to amend Apollonius’ work, and Apollonius in turn revised Book I of the Conics based on their feedback.

Geometry, in short, stands out as a unique case of cumulative and cooperative scientific practice. In contrast, the life sciences present a very different picture. Unlike geometry, this field lacked a unified lexicon and a sufficiently cohesive community to standardize it. As late as the turn of the second century CE, Rufus of Ephesus deemed it necessary to compose a treatise on the terminology used to describe parts of the human body. Only Galen eventually achieved widespread recognition, which led to some degree of standardization. There were no institutional authorities to officially sanction medicine as a public utility, nor any standardized curriculum or certification system for training physicians. This absence of external regulation is common across scientific disciplines. Yet in medicine, unification also failed to emerge from within, as it had in geometry: medical knowledge remained fragmented, and no scientific community with shared theoretical or methodological foundations took shape.

Celsus, writing under the emperor Tiberius, attests in the preface to De medicina to the existence of multiple conflicting schools, notably between empiricist and ‘rationalist’ or ‘dogmatic’ physicians – and even divisions within the latter. The empiricists acknowledged that, alongside autopsy (direct observation by the physician), historia – accounts of observations by other physicians – was fundamental to the constitution of medical knowledge. Their positive evaluation of historia rested not only on anti-relativist assumptions (i.e., that identical phenomena observed by different individuals yield concordant reports worthy of pístis), but also on a view of medicine as the cumulative result of cooperation among physicians across time and space. This view validated the use of libraries and philological work on medical texts – especially the Hippocratic corpus. Nonetheless, empiricists rejected the construction of general theories or the inference of unobservable causes from observable phenomena, as ‘dogmatic’ physicians claimed to do.

To the empiricist and rationalist orientations in medicine were later added others, such as the methodical and pneumatic schools. The relationships between these currents were essentially competitive, not to be mistaken for mere critical engagements with past or contemporary physicians. Such critiques, in fact, are also found in more unified or homogeneous areas of scientific knowledge. Apollonius of Perge, for instance, openly pointed out the limitations of his predecessors – including Euclid and Conon – in their treatment of conic sections, to emphasize the novelty and originality of his own results. Archimedes likewise spoke, on occasion, of pseudo-demonstrations proposed by other geometers, later revealed to be unfounded.

In geography, Strabo defended Homer from Eratosthenes’ criticisms, aligning himself with the classicist revival already underway by the late first century BCE, and advocating for a unified tradition of geographical knowledge capable of progressive augmentation. Ptolemy himself – although not always reliant on previous investigations – acknowledged at the outset of the Almagest (I, 2) that his own demonstrations were based not only on his direct observations, but also on reliable records from both ancient and contemporary sources. In this context, his praise for Hipparchus coexists with critiques of the inaccuracy of some of Hipparchus’ measurements and calculations. Yet such polemics, however sharp, did not entail fundamentally opposing conceptions of mathematical or astronomical inquiry.

Medicine, however, presents a different case. Unlike in mathematics or astronomy, there were economic stakes involved – namely, attracting clientele and ensuring one’s livelihood. This situation was mirrored in technology, particularly military technology. Vitruvius (X, 16, 3 and 6-7) recounts a public exhibition in Rhodes in which a technician, by showcasing the function of a war machine, displaced an architect who was already receiving a public salary and was a native of the city. Such competitions were widespread in the Hellenistic world, especially in cities that employed public physicians, offering them tax exemptions and other privileges. In Ephesus, contests among physicians were held, and winners were listed annually, akin to Olympic victors.

This competitive context is particularly well documented in Rome from the first century BCE to Galen’s era. After initial hostility toward Greek medicine – notably from Cato the Censor – Rome became a major center of attraction for physicians from across the Greek-speaking world. By the end of the second century BCE, this distrust had begun to subside. According to Pliny (XXIX, 12-15), much of the credit for this shift went to Asclepiades of Bithynia, who famously refused an offer to serve at the court of Mithridates – where other physicians were held in high regard – and who was later considered a founder of the methodical school. His success among Rome’s aristocracy stemmed not only from his therapeutic innovations – favoring baths, exercise, and diet over drugs and surgery – but also from his oratorical skill, which, as Cicero notes in De oratore, enabled him to outshine his medical peers in public discourse.

It is worth noting that Nero’s physician, Thessalus, also belonged to the methodical tradition. Soranus, a century later, began his medical education in Ephesus, continued it in Alexandria, and eventually practiced in Rome during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian. Galen himself, after studying in Pergamum, Smyrna, and Alexandria – and having served as physician to gladiators in 157 CE – moved to Rome, where he gained access to elite circles, including Titus Flavius Boethus. In his On Prognosis, Galen recounts the public acclaim following his successful treatment of the elderly Peripatetic philosopher Eudemus. His reputation reached Emperor Marcus Aurelius, who summoned him to Rome in 169 CE, marking the start of Galen’s most prolific phase as a writer. Galen practiced in a society where physicians vied intensely for a wealthy clientele. In the absence of formal accreditation or regulation of medical practice, every school and therapeutic method had to be ‘marketed’ competitively. While therapeutic success certainly played a role, rhetorical ability and cultural refinement were also essential to establishing one’s image as a competent physician, especially before educated audiences in public venues like the Temple of Peace or the Baths of Trajan. It is no coincidence that Galen authored a treatise titled The Best Physician is also a Philosopher.

The interest of a cultivated public in general medical issues is also attested by Plutarch’s Quaestiones convivales – a tradition that harkens back to antiquity. In Plato’s Symposium, for instance, the physician Eryximachus contributes a speech on love from a medical perspective. Among Galen’s strategies for bolstering his reputation and discrediting rivals was the public dissection of animals – including, as he himself recounts in the Anatomicae administrationes, an elephant – as well as monkeys, goats, dogs, and pigs. These demonstrations had not only an instructional and scientific function but also an agonistic and theatrical one. This performative dimension was accompanied by a comprehensive reevaluation of the history of medicine. Galen systematically distributed praise and blame across various schools, constructing an authoritative lineage from Hippocrates to himself, in contrast to the perceived partialities and errors of competing traditions.

The physical proximity of scholars from various disciplines in Alexandria’s Museum and in other Hellenistic and Roman centers fostered exchanges across domains – both at the level of explanatory models and at the level of practical applications. Such intersections were natural among the mathematical and astronomical sciences, whose affinities had already been theorized by Plato and Aristotle. That Euclid wrote also on optics and music theory, and that Eratosthenes cultivated interests in diverse fields, are indicative. Archimedes, likewise, applied mechanical principles to solve strictly geometric problems. One of the most intriguing intersections was between Hellenistic medicine and contemporary technology as exemplified by Ctesibius and Philo of Byzantium. Alongside Herophilus, who devised a water clock calibrated by age to measure the frequency of pulses and assess fever, one must mention Erasistratus, who drew analogies between the heart and water pumps to explain the function of valves, and between motor nerves and torsion springs used in war engines.

Andrew of Carystus, previously mentioned as physician to Ptolemy IV, also contributed to surgical innovation. He devised a machine for setting dislocated femurs, described by both Celsus (VIII, 20, 4) and Galen in his commentary on the Hippocratic On Joints. While reduction techniques were already known to Hippocratic medicine, Andrew’s device introduced new mechanical elements, including the screw, which enabled more gradual and precise application of force. His apparatus remained in use at least until the fourth century CE. As the king’s personal physician, Andrew had direct access to military technologies, particularly those of Philo of Byzantium, and he borrowed both concepts and terminology from them. Interestingly, linguistic borrowing also flowed in the opposite direction: terms from human anatomy were sometimes adopted to describe parts of machines.

Medicine and military technology were connected by reciprocal exchanges and both deeply embedded in the courtly urban environment. While most technicians and physicians continued to operate within the limits of their respective specializations, figures such as Vitruvius in architecture and Galen in medicine theorized the necessity of linking their disciplines to a broader constellation of knowledge. In De architectura, Vitruvius laments that architecture is practiced by uncultivated individuals. According to him, the ideal architect must possess not only knowledge of geometry – for the practical use of ruler and compass – but also of optics, to address problems of lighting; arithmetic, for precise calculations of measurements and costs; astronomy, particularly for constructing sundials; music, for issues related to acoustics; and medicine, to evaluate the salubrity of building sites. However, he specifies that the architect need not attain expert knowledge in these fields, but rather a general familiarity sufficient to integrate them into architectural practice.

Similarly, Galen places at the core of his self-presentation as the model physician his ability to interconnect medicine with other branches of scientific knowledge. In various writings, Galen credits his father – an architect with broad scientific interests – for encouraging him, during his youth in Pergamon, to study disciplines such as geometry, architecture, logistics, arithmetic, and astronomy, followed later by philosophy under teachers from the Stoic, Platonic, Aristotelian, and Epicurean schools. Galen attributes to his mathematical training his ability to resist the factionalism of the philosophical schools and the temptation of skepticism regarding the possibility of knowledge (De libris propriis, 11 in: K XIX 40; De dignotione peccatorum, I, 8 in: K V 41-42). For Galen, these disciplines represent models of genuine scientific knowledge, founded on demonstration and characterized by shared principles and the absence of diaphünía – the discord that, in his view, plagues both philosophy and medicine.

Except for Hippocrates – whom he holds up as the exemplar of the true physician, in part for his ability to integrate astronomy with medical practice – Galen generally avoids aligning himself rigidly with any single medical school. One of his criticisms of the methodists, as stated in De methodo medendi (I, 1-2 in: K X 5, 17), is that they claimed – like Thessalus – that medicine could be taught in just six months, and that aspiring physicians need not study geometry, astronomy, or music. These pronouncements form part of Galen’s rhetorical strategy to establish himself as a learned and authoritative physician. Nevertheless, references to other disciplines in his works sometimes serve more than ornamental or persuasive purposes. In the Anatomicae administrationes and other writings, Galen employs geometric terminology and concepts to render anatomical descriptions more precise. In De usu partium, he invokes the theory of isoperimetric figures – highlighting that the circle has the greatest area among figures with equal perimeter – to explain, echoing Aristotle and Erasistratus, why circular wounds are slowest to heal.

In his commentaries on Hippocratic works such as the Epidemics and the Prognostics, Galen draws on calendrical astronomy to interpret time-related indications regarding the course of illnesses and crises. This includes discussion of the length of the year and the variation of day and night depending on geographical location and season, showing how deeply embedded astronomical concepts were in his understanding of medical temporality.

A particularly noteworthy case is his treatment of optics in relation to vision and the anatomy of the eye in De usu partium (X, 12-15 in: K III 812-841). Initially, Galen hesitated to include demonstrations of optical theorems, aware that such material might deter even competent medical readers. However, he eventually reversed his decision, prompted – according to his account – by a dream in which he was reproached for neglecting the eye, considered the most divine of organs, and thereby offending its providential creator. That Galen felt compelled to invoke a divine vision to justify the inclusion of rigorous optical-geometric content in a medical treatise so strongly marked by theological and teleological elements is telling. It reveals much about the intellectual climate of the second-century CE Roman Empire and the expectations of its educated public concerning medicine, mathematics, and the broader scientific literature. This episode opens an important window onto the cultural reception, dissemination, and preservation of scientific knowledge in antiquity.

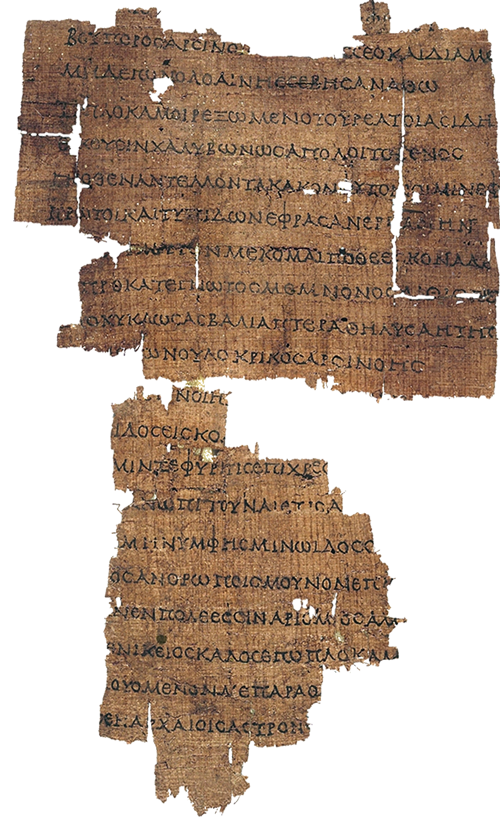

It now becomes necessary to consider the factors that contributed to the dissemination, preservation, or loss of scholarly literature in antiquity. In a context where public and private libraries were frequently subject to destruction – particularly by fire – the survival and circulation of texts depended largely on the repeated manual reproduction of works in multiple copies, initially on papyrus and later on parchment codices. This process, in turn, was tightly linked to patronal demand. With regard to scientific literature, it is clear that general education played a limited role in its transmission and preservation. Mathematics and astronomy were rarely integral to the education of the young, except at rudimentary levels – as demonstrated by Hellenistic-period Egyptian papyri containing school exercises. Even in Rome, Horace (Ars poetica, 325-330) implies that the arithmetic taught to children did not go beyond basic calculations with coins. Advanced scientific literature, therefore, found no audience in such educational contexts.

In the absence of adequate documentation, it is nearly impossible to reconstruct the exact pathways through which individuals attained advanced mathematical knowledge or became mathematicians and astronomers. In many cases, paternal influence appears to have been decisive – this is attested for Archimedes and Galen, and we know that Ipsicles’ father, to whom Book XIV of the Elements is attributed, was himself a mathematician. However, exceptions existed: Ctesibius, for instance, was the son of a barbershop owner (Vitruvius, X, 8, 2), a background unlikely to provide access to technical or scientific training.

In general, interest in the mathematical sciences among the wealthy and educated classes – both in the Hellenistic and Roman worlds – seems to have been neither widespread nor particularly deep. Cicero presents as exceptional figures those who pursued such disciplines: Sextus Pompeius, the uncle of Pompey the Great, who retired from public life to study ethics, law, and geometry (Brutus, 175), or a freedman of Crassus with similar interests. Even more unique was the case, recorded by Plutarch, of a woman – the daughter of Metellus Pius Scipio – who studied mathematics, music, and philosophy (Pompeius, 55).

Plutarch himself, although he studied mathematics extensively in his youth in Athens, eventually abandoned what he deemed an overly specialized discipline (De E apud Delphos, 387f). Some of his writings reveal an interest in astronomical matters, yet mathematics plays virtually no role: in De facie in orbe lunae, the mathematician Menelaus remains virtually silent; and that Plutarch is listed as the author of a work on whether odd or even numbers are superior offers a clear indication of the nature of mathematical questions that might capture his attention.

Cicero, for his part, may have studied geometry with the Stoic philosopher Diodotus, but he confessed to Atticus his discomfort with the mathematical content required to write about geography (Ad Atticum, II, 4, 1; 6, 1). His bitter observation that the tomb of Archimedes had fallen into neglect (Tusculanae disputationes, V, 64-66) and his remark that geometry in Rome was now limited to practical measuring (ibid., I, 5), alongside his note that Latin lacked a specific geometrical vocabulary (Academica, I, 6), should not be read as a call to reverse this trend. Rather, his warning not to waste time on obscure and unnecessary matters like astronomy and geometry – thus neglecting civic duties (De officiis, I, 19) – echoes sentiments attributed to Socrates by Xenophon but also reflects the dominant attitude of Rome’s aristocratic and educated classes.

It is no surprise, then, that we lack records of prominent mathematicians residing in Rome – unlike physicians, whose presence is well attested. Mathematical literature, particularly that addressing complex topics, never reached a general audience; its readership remained limited to a small group of specialists. This may help explain, among other things, the relatively limited circulation of Archimedes’ writings in antiquity, in contrast to the broader dissemination of Euclid’s Elements.

One must also consider another factor that hindered the spread and preservation of scientific literature: the emergence of elementary manuals, treatises, compendia, and encyclopedic works covering specific subjects or broader scientific domains. In some cases, authoritative texts supplanted earlier ones, rendering them obsolete. Such was the fate of many works in the wake of Euclid’s Elements, which consolidated and codified earlier results, thereby displacing the preceding literature. A similar case is Ptolemy’s Syntaxis (Almagest), which established itself as the canonical reference in mathematical astronomy and likely contributed to the loss of Hipparchus’ writings. A different situation arises with Ptolemy’s Geography, which contains primarily catalogs of longitudes and latitudes based on his own astronomical measurements. This work did not directly compete with the more descriptive Geography of Strabo, which in turn had already rendered much earlier material – especially that of Eratosthenes – largely superfluous.

Similarly, the disappearance of most Hellenistic medical literature can likely be attributed to the increasing authority of Galen’s corpus. The same applies to Dioscorides’ De materia medica, whose extensive catalog of some 600 plant species eclipsed earlier pharmacological works, including that of Crateuas from the first century BCE – despite his innovation of including illustrations (Pliny, Naturalis historia, XXV, 8). Elementary treatises on astronomy, such as those by Geminus and Cleomedes, have survived – likely because they steered clear of more advanced topics. In other instances, compendia and encyclopedias supplanted original research, particularly in the Roman and Latin cultural spheres. Varro, a contemporary of Cicero, combined antiquarian interests with Pythagorean numerical speculations in a work entitled Disciplinae, which included introductory treatments – perhaps without formal demonstrations – of geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and music: the disciplines later grouped under the quadrivium.

A similar rationale applies to Celsus’ De medicina, likely intended as part of a broader encyclopedic project, and even more so to Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis historia. Pliny did not compose a specialist treatise confined to a particular field, nor a systematic compendium, but rather – in line with a widespread taste for miscellany and marvels – sought to compile a vast repository of everything contained in the universe, and especially on Earth. His target audience, as he himself states, were the studiorum otiosi: not the learned, but those with the leisure to read. Although he sometimes relied on personal observations, particularly in botany – e.g., in a tour of Antonius Castor’s hortulus – Pliny’s project was fundamentally bibliographic: a book constructed from other books. He claimed to have read some 2,000 volumes (Naturalis historia, I, pref., 17), from which – according to his nephew, Pliny the Younger (Epistulae, III, 5) – he compiled excerpts and notes. In the preface to his work, Pliny boasts that neither any Latin nor any Greek author had attempted such a comprehensive endeavor alone.

The case of Pliny’s Naturalis historia is emblematic of a work largely constructed from other texts, whose very success contributed to the disappearance of many of its sources – works that were often more complex and specialized. This phenomenon did not, of course, eliminate other traditions, such as the zoological and botanical writings of Aristotle and Theophrastus. Although Pliny and Aelianus drew upon them to some extent, these works maintained a fundamentally different structure and purpose, being primarily addressed to a school audience and characterized by an interest in the regularity and systematic nature of natural phenomena. By contrast, the Naturalis historia privileges what is rare, exceptional, or astonishing in nature – those very features that provoke wonder.

Thus, the mere thematic overlap between texts did not automatically determine the fate of certain writings. What also mattered were the methodological approach and the intended audience. Authors of encyclopedic or compendious works, who often wrote in Latin, targeted a different readership than that of scientific treatises produced in Alexandria or other major centers of Hellenistic Greek culture. They did not write for a narrow circle of specialists, but for a broader public. The essential aim of such works was not to advance knowledge by generating new results, but rather to widen the circulation of already existing knowledge – often by simplifying it. That said, these works could nonetheless include original contributions by their authors.

At times, the poetic form helped sustain interest in scientific subjects by rendering them more accessible to a broader and less specialized public. This was especially the case for astronomical and astrological themes. In the cultural milieu influenced by the Library of Alexandria – with its antiquarian and cataloguing tendencies – Eratosthenes collected mythological and popular narratives regarding the origins of constellations. This topic was also dear to Callimachus, as evidenced in his Coma Berenices, where the newly discovered constellation was presented as the transformed curl of Queen Berenice, wife of Ptolemy III Euergetes. Eratosthenes treated this theme in prose in the Catasterisms, but also composed two poetic works on it, Hermes and Erigone. Around the same time – the mid-third century BCE – Antigonus Gonatas, king of Macedonia, asked Aratus of Soli to versify the contents of Eudoxus’ Phenomena, composed a century earlier (Achilles Tatius, In Arati phaenom. comm. fr. 77). This is a typical instance of Hellenistic scholarly poetry with a cataloguing impulse: constellations are grouped and described, and the final portion – anticipating Works and Days by Hesiod – interprets them as signs for meteorological forecasts relevant to agriculture and navigation. Though it is not a work of technical mathematical astronomy – it contains no discussion of planetary motions – its popularity endured. Cicero, in fact, calls Aratus homo ignarus of astronomy (De oratore, I, 69). It is significant that in the following century even Hipparchus, one of antiquity’s most important astronomers, felt compelled to write a commentary on Aratus’ poem – despite many prior commentaries – offering critical corrections that targeted not only Aratus but also, implicitly, the cosmology of Eudoxus. Tellingly, Eudoxus’ original work has been lost, while Aratus’ poem survived, along with Hipparchus’ commentary – the only work of his to reach us. Astronomy as known in Rome resembled Aratus’ poetic presentation more than the mathematical astronomy later codified by Ptolemy. Geography, too, adopted poetic form – as seen in the Periegesis of the Inhabited World by Dionysius Periegetes, composed in Hadrian’s time and based on Eratosthenes’ map. In it, places are evoked not through precise measurements but through geometric and empirical analogies.

The dedication of writings to sovereigns or prominent individuals not only sought their patronage but likely contributed to the survival – and occasionally wider circulation – of those works. Archimedes’ Arenarius is dedicated to Hieron, and the various books of Apollonius’ Conics are prefaced with letters addressed to an Attalus, probably a Pergamene king. Military-technical literature was typically addressed to monarchs or emperors and to their engineers. Biton’s treatise on siege warfare is dedicated to a King Attalus; Apollodorus of Damascus dedicated his work to Trajan. Vitruvius addressed De architectura to the emperor, and Pliny offered the Naturalis historia to Titus, while also addressing it to turbae of farmers, artisans, and studiorum otiosi. According to Aelianus (On Tactical Arrays of the Greeks, I, 2), even Pyrrhus of Epirus and his son Alexander authored treatises on tactics, though none have survived – showing that the prestige of an author did not guarantee the endurance of his works. Apollonius of Citium’s commentary on On Joints by Hippocrates was dedicated to a Ptolemy and included illustrations, preserved in the manuscript that transmitted the text. In the proem, Apollonius treats illustration as standard practice – likely because it enhanced textual clarity, thus serving as a visual commentary and contributing to the work’s survival. Illustrations also accompanied Alexander of Damascus’ Poliorcetica, and, as Pliny notes (XXV, 8), were likely present in pharmacological writings as well.

The dedication of medical works to high-status individuals was also common in Rome. Asclepiades dedicated one work to Mithridates of Pontus and another to the Roman Geminius (Celius Aurelianus, De morbis chronicis, II, 110). Galen addressed many of his writings to fellow physicians, but also to Roman nobles such as Bassus, and sometimes claimed to have written them at their request – as with the Anatomicae administrationes, composed at the urging of the consul Flavius Boethus. Yet counterexamples exist: Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos, an astrological manual that would gain extraordinary popularity in later centuries, was dedicated not to a notable ruler or scholar but to an otherwise unknown Syrian. Nevertheless, dedications to figures outside the author’s disciplinary sphere, as well as the inclusion of illustrations, may have helped texts circulate beyond professional circles. Such practices align with another strategy for publicizing discoveries: inscriptions on monuments. Eratosthenes, for instance, composed an epigram inscribed on a stele to announce his solution to the problem of duplicating the cube – perhaps accompanied by the instrument used, located in a temple, museum, or royal palace. Similarly, Ctesibius dedicated to Arsinoe – a daughter of Ptolemy I – a god-shaped cup with an automatic trumpet mechanism. This object, placed in a temple and revered as sacred, bore a dedicatory epigram engraved on its pedestal.

One of the reasons for the diffusion of astronomy, geography, and music in the Roman world lies in the fact that these disciplines, unlike geometry and other branches of the mathematical sciences, addressed objects and themes more accessible and appealing to the educated public, and were often intertwined with religious and popular beliefs. This is evident, for instance, in Egyptian papyri – sometimes bilingual in Greek and Demotic – that contain numerical tables of the daily positions of celestial bodies and horoscopes, illustrating how the predictive expertise of priests in astronomy continued to be indispensable for rural populations in Roman Egypt well into the second century CE. According to Cicero and Pliny, as early as the mid-second century BCE, the aristocrat Sulpicius Gallus had authored a book – perhaps in Greek – explaining eclipses and planetary distances. It is no coincidence that Cicero himself, despite his limited mathematical expertise, undertook a Latin translation of Aratus’ poem, a gesture later emulated by Germanicus, Augustus’ nephew.

Because of its links to calendrical calculations, astronomy was more palatable than abstract geometrical models of the cosmos, although by the first century BCE a taste for mechanical representations of celestial phenomena had emerged. This is attested by the admiration for Archimedes’ planetarium, preserved from the sack of Syracuse. Julius Caesar himself, in his calendar reform, relied on the astronomer Sosigenes, likely from Alexandria. Pliny (XVIII, 211-212) even mentions a Greek book by Caesar on the stars, perhaps an astro-meteorological calendar, which, however, would not have required profound astronomical expertise. The enduring appeal of astronomy was bolstered by the spread of astrology, which also drew on Babylonian astronomical data. The favorable reception of astrology among educated circles was significantly facilitated by the support of many Stoic philosophers, who embraced doctrines of cosmic sympathy and the causal order of the universe. In Rome, astrology flourished not only through Greek intellectuals but also through native enthusiasts, partly due to its affinity with traditional Etruscan divinatory practices. Notable figures include Nigidius Figulus, known for his interests in divination and magic, and Lucius Tarutius of Fermo, a familiaris of Cicero, described as an expert in “Chaldean calculations” (De divinatione, II, 47, 98).

Astrology’s prominence was further reinforced by the practice of casting horoscopes not only for individuals but also for cities and kingdoms. Varro, for example, allegedly proposed to Tarutius that, if it was possible to predict events from a birth date, it should also be possible to infer the date of birth of Romulus from the events of his life – and thus to determine the founding date of Rome itself (Plutarch, Romulus, 12). The popularity of astrology is also reflected in the Latin poet Manilius’ Astronomica, which explicitly embraces astrological themes. Ptolemy addressed astronomy and astrology in separate works, but insisted that while astronomy can stand independently, astrology must rely on the data and methods of mathematical astronomy. It is not surprising, then, that astrologers were often referred to as mathematicians. In this way, astrology lent additional prestige to astronomy and contributed to sustaining its study.

Lastly, the role of philosophical schools in the dissemination of scientific knowledge and the preservation of scientific texts merits consideration. It should be recalled that ‘physics’ – in the original sense of inquiry into nature – remained, even after Aristotle, a central component of philosophical systems. Roman intellectuals of municipal aristocratic origin, such as Varro, Seneca (with the Naturales quaestiones), and Pliny the Elder, all addressed meteorological and natural phenomena as part of a traditional framework of philosophical concerns, continuing the legacy of Aristotle, Epicurus, and the Stoic Posidonius. For both Seneca and Pliny, the observation of natural phenomena is motivated by a vision of nature as a divine, generative principle. Their texts consistently integrate ethical judgments and critiques of luxury and moral decay, adopting a conception of philosophy as ars vitae – a practical art of living. This moralizing dimension was never absent, even when their writings focused on the marvels and mechanisms of the natural world.

The relationship of philosophy to mathematics, and consequently its contribution to the dissemination or loss of mathematical literature, was more complex and less uniform. Whereas medicine, military technology, and architecture were associated with defined patrons and purposes – and thus retained a quasi-artisanal status – mathematics never acquired a comparable professionalization. Disciplines such as geometry and optics were cultivated either by individuals in a personal capacity or within philosophical schools. Mathematics was held in high esteem in the Platonic tradition and remained relevant within the Aristotelian school, though there is no evidence that Euclid derived his axioms directly from Aristotle’s theory of science, nor that he adopted a syllogistic deductive model.

In the Hellenistic age, a widespread view emerged that philosophical speculation and scientific inquiry had become geographically and institutionally distinct – the former centered in Athens, the latter in Alexandria. It is true that the works of mathematicians active in Alexandria, Syracuse, or Pergamum reveal little engagement with the theoretical and methodological debates of contemporary philosophy. Archimedes, for instance, distinguishes between analysis (problem-solving) and demonstration, employing a vocabulary reminiscent of Aristotelian and Stoic terminology – but this does not imply philosophical alignment or dependence. Notably, the logic of discovery – how mathematical knowledge is generated – was not a subject of philosophical discussion in this period. While mathematicians accepted axiomatic structures without question, philosophers such as the Epicureans not only questioned them but also engaged with geometry to refute it. For Epicurus, who held that mathematical disciplines did not contribute to wisdom, geometry was irrelevant or even misleading.

During his teaching period in Lampsacus, before founding his school in Athens in 306 BCE, Epicurus had among his disciples Polyenus, who polemicized with the mathematicians of Cyzicus (followers of Eudoxus) and ultimately declared all geometry to be false (Cicero, Academica, II, 33, 106). This stance, which may have already been Epicurus’ own, likely stemmed from the perceived incompatibility between Epicurean atomism and the assumption of infinite divisibility underlying Eudoxian and Euclidean geometry. A similar position was taken by the Epicurean Philonides, whose life is partially reconstructed from a Herculaneum papyrus (Papiri Herculanenses 1044). Coming from a wealthy family and trained in mathematics, Philonides was a native of Laodicea (in Syria) and maintained relations with the Seleucid court, specifically Antiochus IV Epiphanes and Demetrius I Soter. He also maintained correspondence with Apollonius of Perge and with Basilides, head of the Epicurean school in Athens in the early second century BCE, who shared his interest in mathematics.

Traces of a work on geometry by the Epicurean Demetrius Lacon are found in a papyrus (Papiri Herculanenses 1061), where he discusses, with the aid of figures, certain propositions from Book I of Euclid’s Elements, particularly those employing the principle of infinite bisection of a segment, likely with critical intent. Demetrius’ friend, Zeno of Sidon, was a scholar of the Epicurean school in the early decades of the first century B.C. in Athens, where he was visited in his old age by Cicero and Atticus. According to Proclus’ commentary on Euclid (199, 1-14; 214, 15-218, 11), Zeno aimed to dismantle geometry as a whole, arguing that even if Euclid's principles are admitted, no demonstration can be derived from them without making further assumptions. This does not imply that Zeno accepted Euclid’s axioms and sought merely a methodological critique aimed at recasting Euclidean geometry more rigorously by adding new axioms; rather, it was a hypothetical concession to his opponent, intended to demonstrate the chronic incompleteness of Euclid's axiomatic system. It is difficult to argue, as has sometimes been done, that these Epicurean criticisms led to the construction of an alternative geometry compatible with Epicurean physics, especially since no trace of such a system exists. Moreover, mathematicians – including Archimedes – in the extant writings, do not explicitly or theoretically address the issue of indivisibles that troubled philosophers. The real target of Epicurean criticism was not only Euclidean geometry itself but particularly the positive evaluation and use of Euclidean geometry by other philosophical schools as a model of certain knowledge.